Next: 8. Using functions and Up: 1 The Pascal language Previous: 6. Expressions

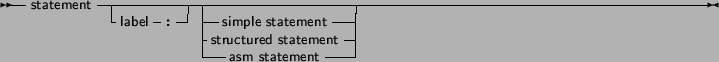

A label can be an identifier or an integer digit.

Statements

Of these statements, the raise statement will be explained in the chapter on Exceptions (chapter Exceptions)

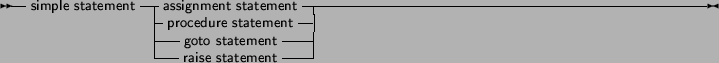

Simple statements

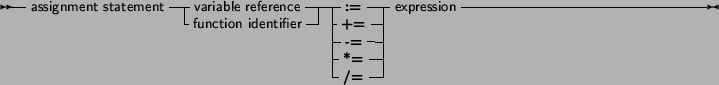

In addition to the standard Pascal assignment operator ( := ), which simply replaces the value of the varable with the value resulting from the expression on the right of the := operator, Free Pascal supports some c-style constructions. All available constructs are listed in table (assignments) .

Assignments

Remark: These constructions are just for typing convenience, they don't generate different code. Here are some examples of valid assignment statements:

X := X+Y;

X+=Y; { Same as X := X+Y, needs -Sc command line switch}

X/=2; { Same as X := X/2, needs -Sc command line switch}

Done := False;

Weather := Good;

MyPi := 4* Tan(1);

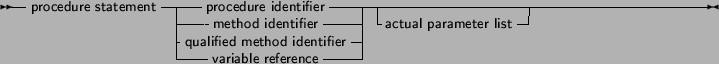

The Free Pascal compiler will look for a procedure with the same name as given in the procedure statement, and with a declared parameter list that matches the actual parameter list. The following are valid procedure statements:

Procedure statements

Usage;

WriteLn('Pascal is an easy language !');

Doit();

When using goto statements, you must keep the following in mind:

Goto statement

label jumpto; ... Jumpto : Statement; ... Goto jumpto; ...

Conditional statements come in 2 flavours :

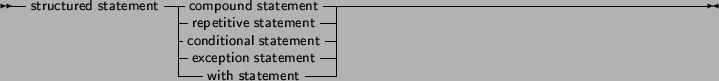

Structured statements

Repetitive statements come in 3 flavours:

Conditional statements

The following sections deal with each of these statements.

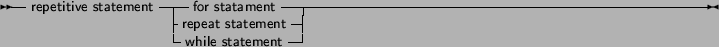

Repetitive statements

Compound statements

![\begin{syntdiag}\setlength{\sdmidskip}{.5em}\sffamily\sloppy \synt{compound\ statement}

\lit*{begin}

\<[b] \synt{statement} \\ \lit* ; \>

\lit*{end}\end{syntdiag}](img93.png)

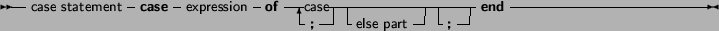

The constants appearing in the various case parts must be known at compile-time, and can be of the following types : enumeration types, Ordinal types (except boolean), and chars. The expression must be also of this type, or a compiler error will occur. All case constants must have the same type. The compiler will evaluate the expression. If one of the case constants values matches the value of the expression, the statement that follows this constant is executed. After that, the program continues after the final end. If none of the case constants match the expression value, the statement after the else keyword is executed. This can be an empty statement. If no else part is present, and no case constant matches the expression value, program flow continues after the final end. The case statements can be compound statements (i.e. a begin..End block).

Case statement

![\begin{syntdiag}\setlength{\sdmidskip}{.5em}\sffamily\sloppy \synt{case}

\<[b] ...

...onstant} \end{displaymath} \\

\lit* ,

\>

\lit* :

\synt{statement}\end{syntdiag}](img95.png)

Remark: Contrary to Turbo Pascal, duplicate case labels are not allowed in Free Pascal, so the following code will generate an error when compiling:

Var i : integer; ... Case i of 3 : DoSomething; 1..5 : DoSomethingElse; end;The compiler will generate a Duplicate case label error when compiling this, because the 3 also appears (implicitly) in the range 1..5. This is similar to Delhpi syntax.

The following are valid case statements:

Case C of

'a' : WriteLn ('A pressed');

'b' : WriteLn ('B pressed');

'c' : WriteLn ('C pressed');

else

WriteLn ('unknown letter pressed : ',C);

end;

Or

Case C of

'a','e','i','o','u' : WriteLn ('vowel pressed');

'y' : WriteLn ('This one depends on the language');

else

WriteLn ('Consonant pressed');

end;

Case Number of

1..10 : WriteLn ('Small number');

11..100 : WriteLn ('Normal, medium number');

else

WriteLn ('HUGE number');

end;

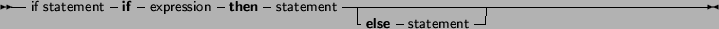

The expression between the if and then keywords must have a boolean return type. If the expression evaluates to True then the statement following then is executed.

If then statements

If the expression evaluates to False, then the statement following else is executed, if it is present.

Be aware of the fact that the boolean expression will be short-cut evaluated. (Meaning that the evaluation will be stopped at the point where the outcome is known with certainty) Also, before the else keyword, no semicolon (;) is allowed, but all statements can be compound statements. In nested If.. then .. else constructs, some ambiguity may araise as to which else statement pairs with which if statement. The rule is that the else keyword matches the first if keyword not already matched by an else keyword. For example:

If exp1 Then

If exp2 then

Stat1

else

stat2;

Despite it's appearance, the statement is syntactically equivalent to

If exp1 Then

begin

If exp2 then

Stat1

else

stat2

end;

and not to

{ NOT EQUIVALENT }

If exp1 Then

begin

If exp2 then

Stat1

end

else

stat2

If it is this latter construct you want, you must explicitly put the

begin and end keywords. When in doubt, add them, they don't

hurt.

The following is a valid statement:

If Today in [Monday..Friday] then

WriteLn ('Must work harder')

else

WriteLn ('Take a day off.');

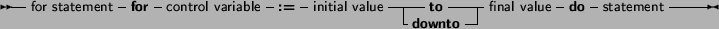

Statement can be a compound statement. When this statement is encountered, the control variable is initialized with the initial value, and is compared with the final value. What happens next depends on whether to or downto is used:

For statement

Remark: Contrary to ANSI pascal specifications, Free Pascal first initializes the counter variable, and only then calculates the upper bound.

The following are valid loops:

For Day := Monday to Friday do Work;

For I := 100 downto 1 do

WriteLn ('Counting down : ',i);

For I := 1 to 7*dwarfs do KissDwarf(i);

If the statement is a compound statement, then the Break and Continue reserved words can be used to jump to the end or just after the end of the For statement.

This will execute the statements between repeat and until up to the moment when Expression evaluates to True. Since the expression is evaluated after the execution of the statements, they are executed at least once. Be aware of the fact that the boolean expression Expression will be short-cut evaluated. (Meaning that the evaluation will be stopped at the point where the outcome is known with certainty) The following are valid repeat statements

Repeat statement

![\begin{syntdiag}\setlength{\sdmidskip}{.5em}\sffamily\sloppy \synt{repeat\ state...

...<[b] \synt{statement} \\ \lit* ; \>

\lit*{until}

\synt{expression}\end{syntdiag}](img102.png)

repeat

WriteLn ('I =',i);

I := I+2;

until I>100;

repeat

X := X/2

until x<10e-3

The Break and Continue reserved words can be used to jump to

the end or just after the end of the repeat .. until statement.

This will execute Statement as long as Expression evaluates to True. Since Expression is evaluated before the execution of Statement, it is possible that Statement isn't executed at all. Statement can be a compound statement. Be aware of the fact that the boolean expression Expression will be short-cut evaluated. (Meaning that the evaluation will be stopped at the point where the outcome is known with certainty) The following are valid while statements:

While statements

I := I+2;

while i<=100 do

begin

WriteLn ('I =',i);

I := I+2;

end;

X := X/2;

while x>=10e-3 do

X := X/2;

They correspond to the example loops for the repeat statements.

If the statement is a compound statement, then the Break and Continue reserved words can be used to jump to the end or just after the end of the While statement.

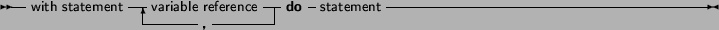

The variable reference must be a variable of a record, object or class type. In the with statement, any variable reference, or method reference is checked to see if it is a field or method of the record or object or class. If so, then that field is accessed, or that method is called. Given the declaration:

With statement

Type Passenger = Record

Name : String[30];

Flight : String[10];

end;

Var TheCustomer : Passenger;

The following statements are completely equivalent:

TheCustomer.Name := 'Michael'; TheCustomer.Flight := 'PS901';and

With TheCustomer do begin Name := 'Michael'; Flight := 'PS901'; end;The statement

With A,B,C,D do Statement;is equivalent to

With A do With B do With C do With D do Statement;This also is a clear example of the fact that the variables are tried last to first, i.e., when the compiler encounters a variable reference, it will first check if it is a field or method of the last variable. If not, then it will check the last-but-one, and so on. The following example shows this;

Program testw;

Type AR = record

X,Y : Longint;

end;

PAR = Record;

Var S,T : Ar;

begin

S.X := 1;S.Y := 1;

T.X := 2;T.Y := 2;

With S,T do

WriteLn (X,' ',Y);

end.

The output of this program is

2 2Showing thus that the X,Y in the WriteLn statement match the T record variable.

Remark: If you use a With statement with a pointer, or a class, it is not permitted to change the pointer or the class in the With block. With the definitions of the previous example, the following illiustrates what it is about:

Var p : PAR; begin With P^ do begin // Do some operations P:=OtherP; X:=0.0; // Wrong X will be used !! end;The reason the pointer cannot be changed is that the address is stored by the compiler in a temporary register. Changing the pointer won't change the temporary address. The same is true for classes.

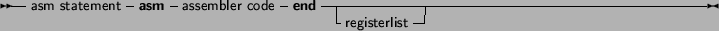

More information about assembler blocks can be found in the Programmers' guide. The register list is used to indicate the registers that are modified by an assembler statement in your code. The compiler stores certain results in the registers. If you modify the registers in an assembler statement, the compiler should, sometimes, be told about it. The registers are denoted with their Intel names for the I386 processor, i.e., 'EAX', 'ESI' etc... As an example, consider the following assembler code:

Assembler statements

![\begin{syntdiag}\setlength{\sdmidskip}{.5em}\sffamily\sloppy \synt{registerlist}

\lit*[

\<[b] \synt{string constant} \\ \lit*, \>

\lit*]\end{syntdiag}](img106.png)

asm Movl $1,%ebx Movl $0,%eax addl %eax,%ebx end; ['EAX','EBX'];This will tell the compiler that it should save and restore the contents of the EAX and EBX registers when it encounters this asm statement.

Free Pascal supports various styles of assembler syntax. By default, AT&T syntax is assumed. You can change the default assembler style with the {$asmmode xxx} switch in your code, or the -R command-line option. More about this can be found in the Programmers' guide.